From Research to Reality

Three Challenges of Running a Research-led Design Practice

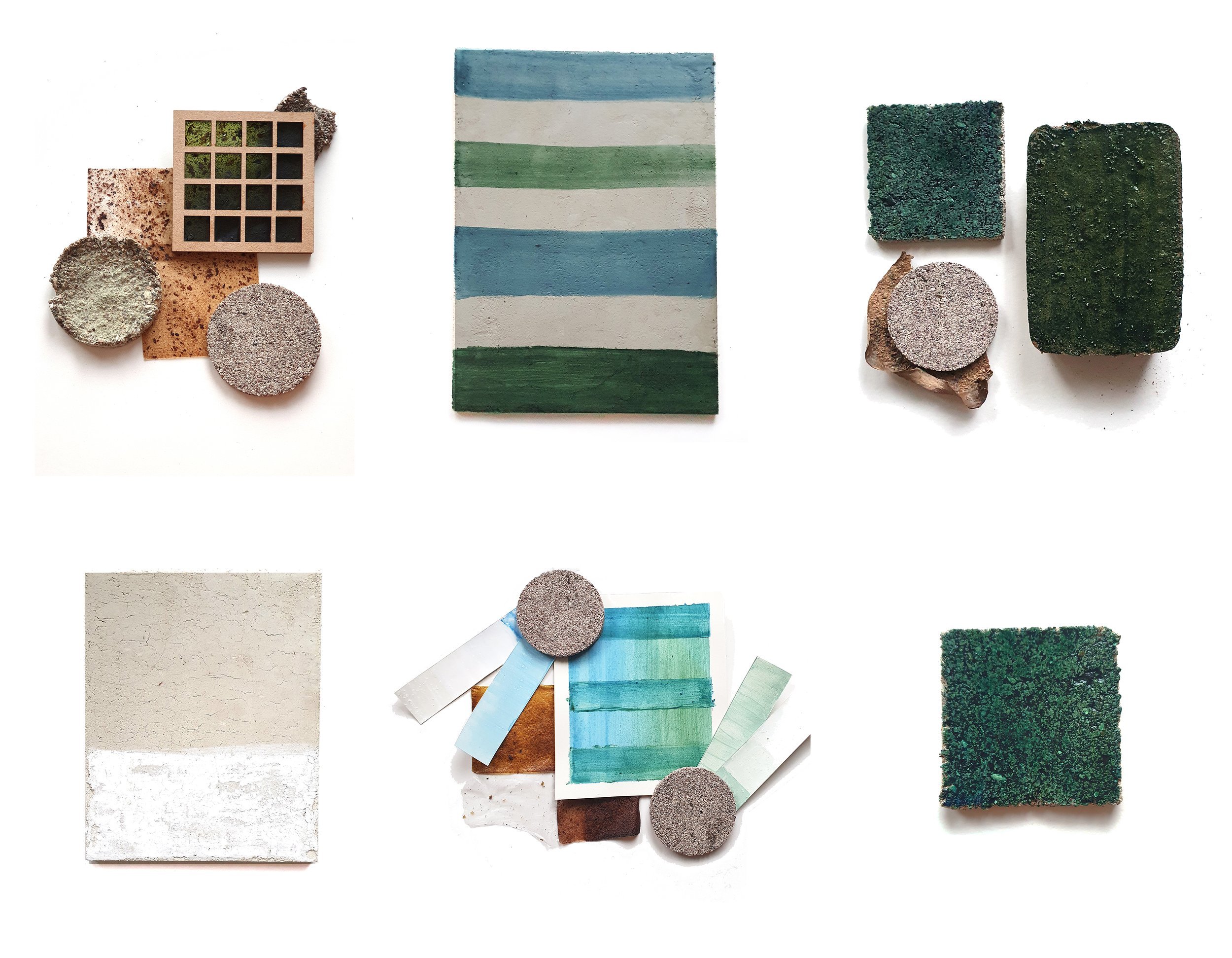

Ongoing Seaweed research by Kathryn Larsen, Studio Kathryn Larsen. (Seaweed Bioplastics, Shellcrete, Seaweed Clay Plaster and Seaweed Paint).

OPINION

Kathryn Larsen, founder of Studio Kathryn Larsen

As experimentation with natural materials has become more and more popular for designer students, many of us are working with lab coats. Or, in my case, with measuring spoons and a stovetop in my kitchen. The designer has become a twenty-first century inventor, testing new materials and processes from the ground up. The allure of discovery and newness can be intoxicating, especially when intertwined with ideas like “saving the planet” and “biodegradable design”.

Unfortunately, the reality after graduation isn’t always pleasant. In my experience, there are three key issues with running a sustainable, research-led design practice that makes for a rough transition from school to practice.

Ongoing research with seaweed, seagrass, and shells by Kathryn Larsen, Studio Kathryn Larsen. Photography by Sarah Tulej.

1. Plagiarism and Design-Theft

In science, you are supposed to delve deep into your research background, find a knowledge gap, and investigate. Your resulting research and methodology should be structured, and the work checked for plagiarism. If you are writing a peer-reviewed article, you will undergo a lengthy process of writing and rewriting, having citations and sources scrutinized, with everything run through a fine-toothed comb.

In design, you are encouraged to reference others’ works. However, as Picasso once said, “Good designers copy, but great designers steal.”

If your research work as a designer becomes trendy enough - yes, other people will steal it. I have sometimes been excluded from funded research projects centred around my work, seen winning competition entries steal my prototype designs and students who copy my words without attribution.

I’m not the only designer to experience this. As I’ve opened up about my experiences with plagiarism, others have come forth with horrible stories about both academic as well as practice-based theft. It’s not always nobodies either- it’s oftentimes done by academic advisors to students and established companies to smaller individuals.

At the same time, as a designer, you are pressured to be open-source. If you keep some formulations or designs a “trade secret”, you are looked down upon. It’s a fine line to balance between giving, sharing, and protecting your work. Which brings me to my next point.

2. Someone Has to Pay

The people that can afford to avoid marketing their own research and work (thus leaving it less vulnerable to being stolen) are people with wealth and connections, either private or institution-based. The rest of us are left seeking funding for our research and constantly looking for resources to help patent and protect ideas. That means constantly writing grant applications for art residencies, sharing our research online in the hopes it catches someone’s attention, and marketing it. It’s tough to get a grant or other partners interested in supporting your work if no one has ever heard of you.

In my case, it’s taken me over four years of marketing, testing on top of my kitchen table, and going back to school for a master’s degree to be able to fully start-up. Businesses are sometimes more open to helping students with a research project connected to a school because the school name is good for them. They are less likely to help a new graduate with a “good idea” because it’s a significantly higher risk.

In order to get proof of concept on many of my ideas, I worked two jobs. After formally establishing my business in October 2021, I worked over one hundred hours a week between school, a part-time job, and my own business. I was finally able to quit my part-time job after six months of this. Someone has to pay, and if you can’t line up VC funding or a grant, you will be paying with your own time and money.

3. When Research also Exploits

A common trend at the moment for sustainable designers is to draw inspiration from TEK – traditional ecological knowledge. This is often a form of knowledge that has been historically excluded by the scientific community, as it is often passed down orally through hundreds of years.

Much of my own work is built from vernacular construction techniques. These techniques were historically denigrated as primitive, as they were not designed by an architect- a gentleman’s profession, as opposed to a builder, which was a labourer’s profession.

As a result, I do my best to structure my research in a way that acknowledges the communities and peoples this knowledge comes from and credit the people who have taught me this knowledge.

This research can often be emotionally charged, as it is tied to heritage, memory and tradition. In my case, I often interview people in their native language and try to keep my material research contained to countries I have lived in, where I can understand the political and social implications of working with these histories.

When I do not have experience in the country I am working in, I usually focus on collaborating with locals from all different backgrounds, which helps increase my awareness of my own blind spots. It is a wonderful feeling to know that I can make space for others at the table and celebrate different voices, as design and academia have often excluded many without the “right education” from participating.

Given all this, it is shocking to see many European and American designers today with open ignorance towards these sensitive issues- who not only take inspiration from TEK but pretend it is their own discovery. They erase the years of history and traditions in order to be heralded as a sustainable genius, and they do not put any effort into working with the communities they are profiting from.

This loops back into number one for me. When people silently steal my work, they aren’t just stealing my words and ideas. They are also stealing the credit and names of the people who have given me their trust and their knowledge- the very people who are mentioned in my project documentation, my lectures, and my papers.

Despite all these challenges of working with research-based design practice, it is a rewarding one and one that gives me much joy. For those that love to learn and care about many different details, I firmly believe that investing in research and innovation can make a positive difference. After all, design and architecture silently impact every moment of our day-to-day life. It’s likely if you noticed a design, it’s because it needs to be improved.

Ongoing Research With Seaweed, Seagrass, And Shells By Kathryn Larsen, Studio Kathryn Larsen. Photography By Sarah Tulej.